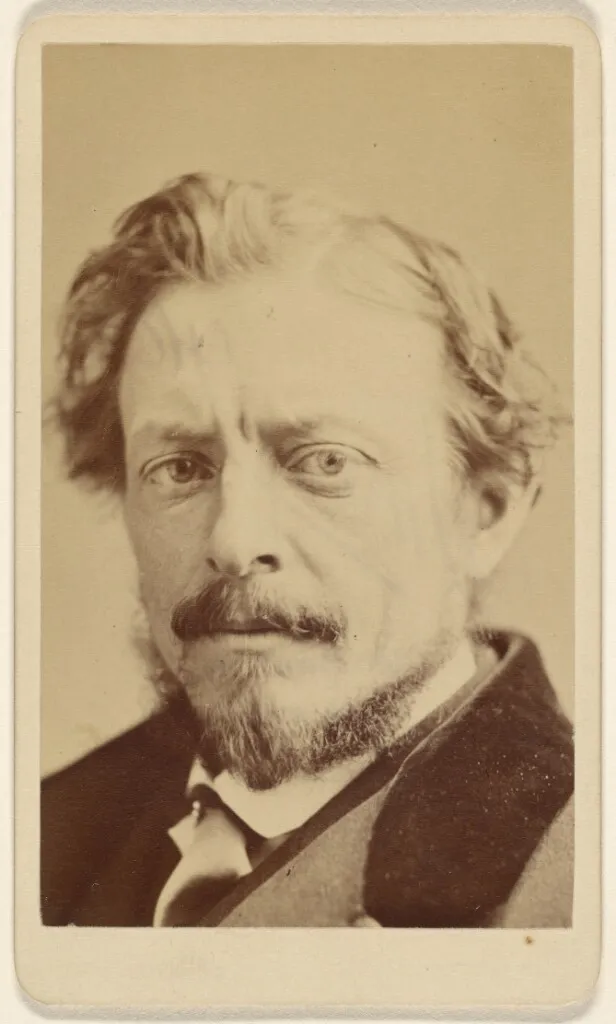

Samuel Colman was 19th century painter, draftsman, designer, watercolorist, and printmaker. He is best known as a painter of expansive Hudson River School landscapes, but also scenes of the American West and Europe. His most recognizable work is unquestionably Storm King on the Hudson (1866), but he was a restless and varied artist who experimented with many different styles and mediums, including etching.

Colman was born in 1832, in Portland, Maine into a family of Swedenborgian booksellers. His father was a publisher and bookstore owner who is remembered by bibliophiles for publishing Hyperion, by a then-unknown Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. His mother was a prolific author and editor of children's stories, including the "Lulu" series.

Importantly for the artist's future career, his uncle William Colman was the properieter of Colman's Literary Rooms, a New York bookseller that doubled as an art gallery. In 1825 the store would become the first place to display and sell works by Thomas Cole, the progenitor of the Hudson River School and the most influential American artist of the first half the 19th century.

Colman spent his early years moving between Portland, Boston, and New York as his father pursued various business opportunities. While affording the family a high standard of living, these endeavors were broadly unsuccessful. By 1850 his father had ceased publishing under his own name and the family had permanantly relocated to New York. The move may have been prompted by the failing health of William Colman the subsequent liquidation of Colman's Literary Rooms.

The younger Colman wasted little time establishing himself in the artistic circles of mid-century New York. He exhibited at the National Academy of Design for the first time in 1851 and by 1854 he was already an Associate Member. Among his friends were noted artists such as James David Smillie, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and Aaron Draper Shattuck, who went on to marry Colman's younger sister Marian. Colman was also well-acquianted with Asher B. Durand, the elder statesman of the New York scene, and painted alongside him on at least one trip to the White Mountains. Colman's earliest works bearing a strong resemblance to Durand's.

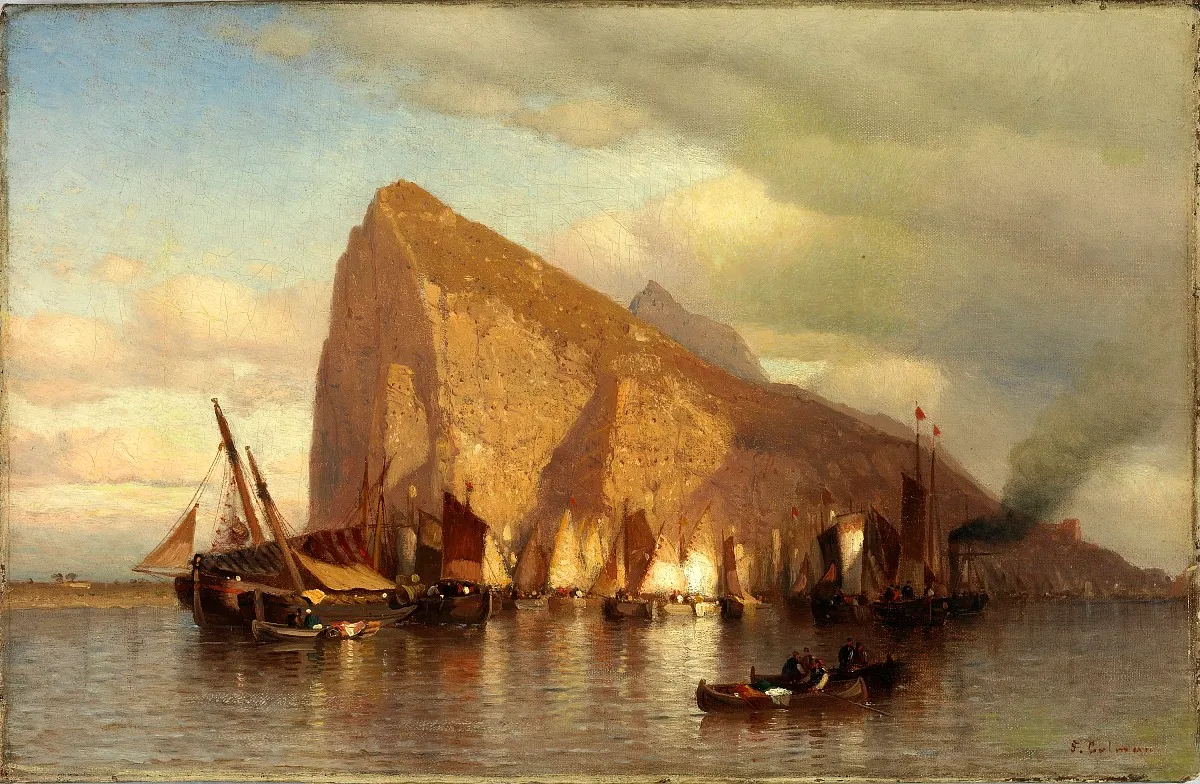

In 1860, at the age of 28, Colman departed on a grand tour of Europe. While he was abroad, the Civil War began and he made the decision to cut the journey short. The trip, however abbreviated, would inspire many of Colman's early masterpieces, including Clearing Storm at Gibraltar. After returning, Colman avoided the draft, presumably by paying the $300 "commutation fee". Meanwhile, his elder brother William, a veteran of the Mexican-American War, fought and was killed at the Battle of Corinth.

The war years were a time of tremendous personal achievement for Colman. In 1862 he married Anne Lawrence Dunham, daughter of Edward Wood Dunham, a fabulously wealthy New York banker. The marriage secured for Colman financial freedom and a place in the upper echelons of New York Society. It also connected him to a fourteen-year-old Louis Comfort Tiffany, a cousin of Anne's by marriage, who would be an important collaborator later in life. Two years after marrying Colman was made a full member of the National Academy of Design and inducted into the Century Association, a prestigious New York social club.

The remainder of the 1860's and 1870's were extraordinarily productive for Colman. In 1864 he held his first major sale at Snedecor Gallery, showing alongside painters Aaron Draper Shattuck and Jervis McEntee. Over the next few years he would paint major masterpieces, including Storm King on the Hudson. Then, just as he was reaching his zenith as an oil painter, he began to experiment with watercolor. In 1866 he cofounded the American Society of Painters in Water-Colours, which would later be become the American Watercolor Society.

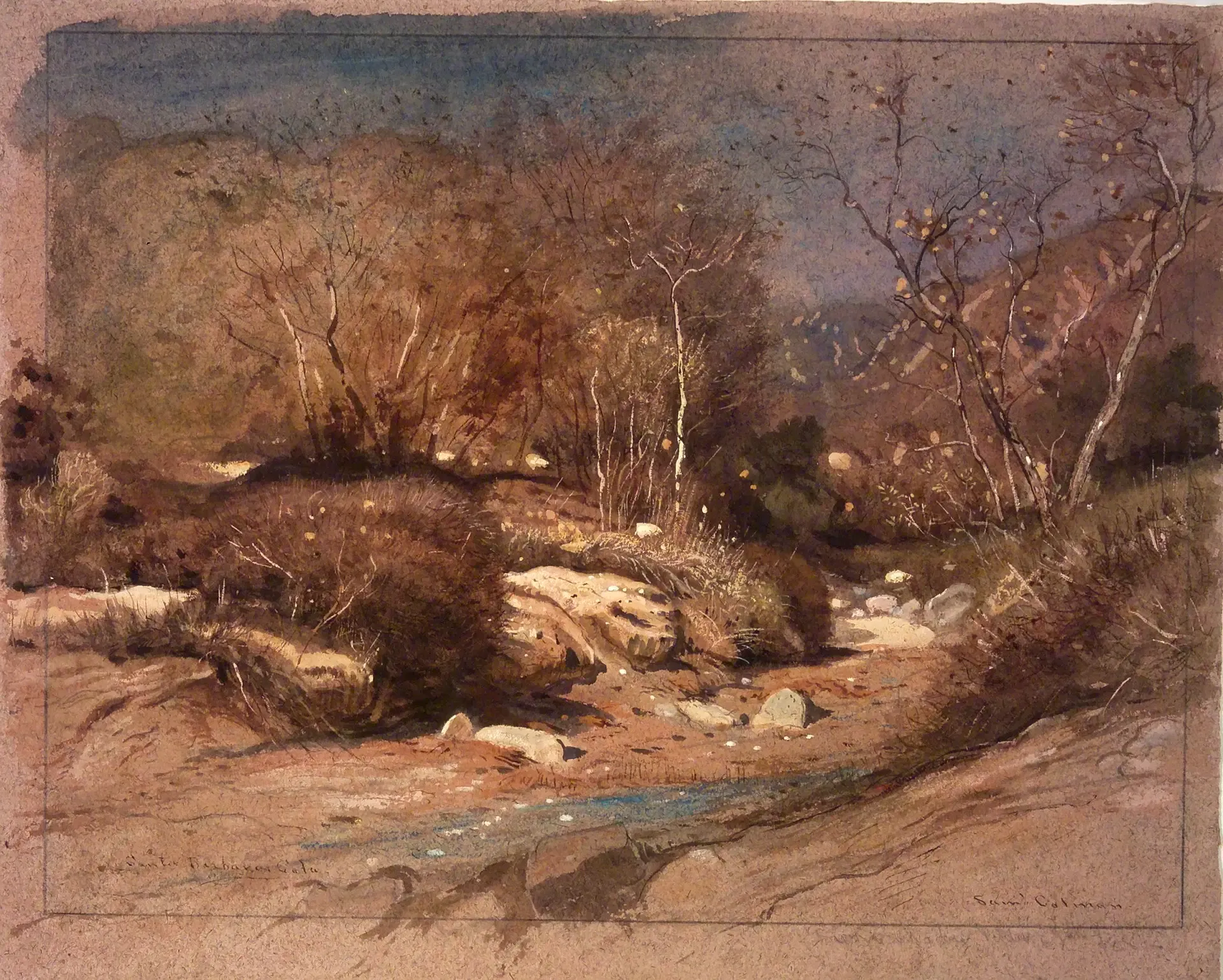

Colman and his wife traveled widely. Some of his's most remarkable pictures, in both oil and watercolor, were inspired by trips to the American West. In 1870 they would travel as far west as Utah. In 1871 they returned to Europe. This time Colman's grand tour would not be cut short. They stayed three-and-a-half years, traveling across the continent and even into North Africa.

In 1875 Colman held a second major show at Snedecor Gallery. It was around this time (and possibly at this event) that he met the ultra-wealthy industrialist Henry Osborne Havemeyer. This relationship would profoundly alter the trajectory of the artist's career. Colman would share with Havemeyer his burgeoning love of decorative arts, including Asian pottery and textiles. Years later, to Colman and Louis Comfort Tiffany would collaborate to design the interiors of Havemeyer's landmark Manhattan mansion. Colman himself would amass a celebrated collection of Asian art, a portion of which he would later gift to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1877 Colman took up etching and became a founding member of the New York Etching Club. With the "etching revival" already well underway in France and England, and New York artists increasingly traveling abroad, it was only a matter of time before the trend reached the New York. A prolific draughtsman, Colman seems to have been drawn the spontaneity of etching. Many of his etched works have a loose, curvilinear style that is characteristic of his drawings, but very different from his oil paintings. While Colman would go on to etch more than fifty plates, his prints have never achieved the same recognition as those of some of his peers, notably his close friends and traveling companions Thomas and Mary Nimmo Moran.

Colman would paint and etch throughout the 1880's and 1890's, though his output would slow as he passed his 50th year. In 1884 he and his wife decamped from New York to an ornate home they had constructed in Newport, Rhode Island. Colman became more active as a decorator, working closely with Tiffany on the Havemeyer mansion and other projects.

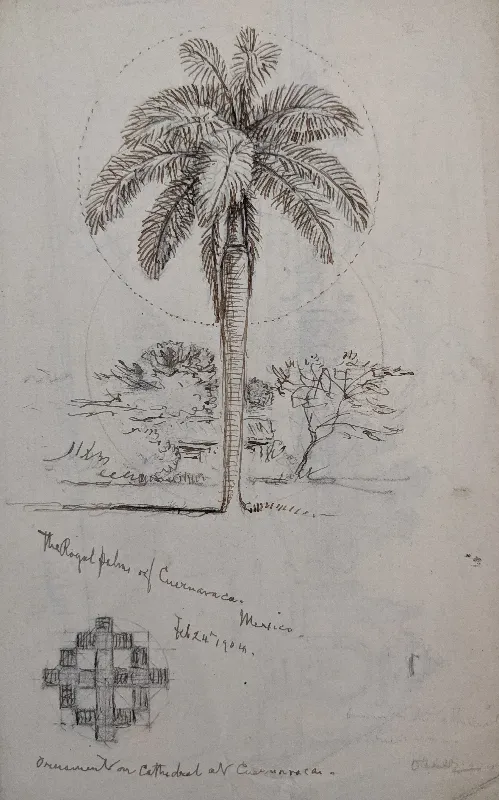

Anne died in 1902 after a long illness. A year later Colman remarried to Lillian Margarat Gaffney. Around this time he also began to part ways with significant parts of his collection, selling Asian art, paintings by other American artists, and his own paintings. In the middle of the decade he and Lillian sold the Newport house and moved back to New York. They also traveled together, first to Mexico and then to Canada. Colman produced many drawings and occasional watercolors documenting their travels. Then, in 1908, at the age of 76, he fathered a son, another Samuel Colman.

Colman would devote much of the final twenty years of his life to work on two esoteric books of art theory: Nature's Harmonic Unity and Proportional Form. Then, in 1920, at the age of 88, Colman died in New York.

After his death, Lillian would continue to disperse his art. In 1927 she sold a large collection at Anderson Galleries and in 1939 she donated more than 150 drawings to the Cooper Hewitt. The latter bequest remains the single largest collection of Colman's work in a public institution. Colman himself would be largely forgotten until a 1976 article in the American Art Review revitalized interest in his work.

Colman's work is often overshadowed by other artists of the period. Museum-goers are more likely to recognize the work of Asher B. Durand, George Inness, or Winslow Homer. But Colman's story is tightly threaded into the artistic story of 19th century America. From the rise of the Hudson River School, to the boom of the etching revival, to his knack for satisfying the orientalist fashion of the robber barons, Colman's life knits together critical developments in the history of American art.